Quartz - SiO2

Quartz is the second most abundant mineral in Earth's continental crust, after feldspar. Its crystal structure is a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon-oxygen tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tetrahedra, giving an overall chemical formula of SiO2. Quartz is one of the more common rock forming minerals, it occurs in siliceous igneous rocks such as volcanic rhyolite and plutonic granitic rocks. It is common in metamorphic rocks at all grades of metamorphism, and is the chief constituent of sand. Because it is highly resistant to chemical weathering, it is found in a wide variety of sedimentary rocks.SiO2 polymorph:

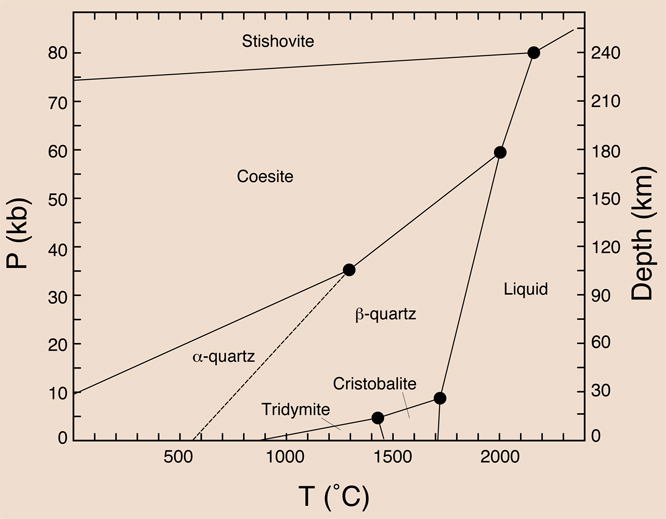

• (α)-Quartz: stable below 573°C

• (β)-Quartz: stable from 573 to 870°C

• (β)-Tridymite: never stable, exists metastably below 117°C

• (α)-Tridymite: stable from 867°C to 1470°C

• (α)-Cristobalite: never stable, exists metastably below 267°C

• (β)-Cristobalite: stable from 1470°C to 1723°C

• Coesite: high-pressure phase found in meteor impact craters, stable at pressures of 2-3GPa and from 700 to 1700°C

• Stishovite: high-pressure phase found in meteor crater, stability field unknown.

• Lechatelierite: is a very rare, natural form of silica that lacks a definitive crystal structure. It is amorphous and considered a natural glass, and is scientifically classified as a mineraloid. Lechatelierite forms naturally by very high temperature especially during lightning strike or during high pressure shock metamorphism due to meteorite impact and is a common component of a type of glassy ejecta called tektites.

During the transition from a α- to a β-variant the atoms in the crystal lattice only get slightly displaced relative to each other, but they don't change places inside the crystal lattice. Because these α-β-transitions are only based on alterations of the angles and the lengths of the chemical bonds, they take place instantaneously. Such a phase transition is generally called displacive, as it only requires relative displacements of the atoms without the need to break chemical bonds. Because the angular Si-O-Si bonds get straightened out, the high-temperature silica polymorphs all possess a higher symmetry than their low-temperature counterparts.

All the other transitions of one silica polymorph into another (like from β-quartz to β-tridymite) require the chemical bonds to be broken up and reconnected to alter the crystal structure; such a transition is called reconstructive. In general, complete reconstructive transitions between polymorphs need a lot of time. Quick changes in temperature do not allow for the complete rebuilding of the crystal structure, and the transition will be skipped.

Fig.1: Silica Phase Diagram

Optical Properties:

• Form: In plutonic rocks is typically anhedral and interstitial as a late-forming mineral. Vermicular blebs are common in graphic intergrowth with K-Feldspar. In volcanic rocks quarz phenocrysts are often euhedral as stubby, doubly terminated, often showing rounding or embayment of resorption.

• Color: Colorless.

• Relief: Low.

• Interference colors: I gray to I white.

Bibliography

• Cox et al. (1979): The Interpretation of Igneous Rocks, George Allen and Unwin, London.

• Howie, R. A., Zussman, J., & Deer, W. (1992). An introduction to the rock-forming minerals (p. 696). Longman.

• Le Maitre, R. W., Streckeisen, A., Zanettin, B., Le Bas, M. J., Bonin, B., Bateman, P., & Lameyre, J. (2002). Igneous rocks. A classification and glossary of terms, 2. Cambridge University Press.

• Middlemost, E. A. (1986). Magmas and magmatic rocks: an introduction to igneous petrology.

• Shelley, D. (1993). Igneous and metamorphic rocks under the microscope: classification, textures, microstructures and mineral preferred-orientations.

• Vernon, R. H. & Clarke, G. L. (2008): Principles of Metamorphic Petrology. Cambridge University Press.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)